SPAC1: NOT JUST WARM UP ANYMORE

I love SPAC.

The lawn, the lot. The park, the palace. The people. It’s a homecoming, almost as regular on the 3.0 schedule as Dick’s. It’s a thing. The only time we don’t get SPAC is when there’s a festival, and that is wholly forgivable.

It wasn’t always that way. This is a 3.0 tour development. Prior to this run, Phish had played here 17 times -- 16 headliners and an opener for Santana -- but only thrice in 1.0. Our more-or-less annual independence jaunt to ‘Toga is a new staple on the calendar, relatively speaking. The toney town might not have worked for us in the mid-to-late ‘90s. Or, more likely, the stop did not make sense if we were annually festivaling in the region. But for now, this is a town with not only a pool and a pond, but also springs, and a spa. And in recent years, our traveling contingent has been warmly welcomed to whichever of the above we can afford.

MANN2 RECAP: SLOW YOUR ROLL

The trajectory of this summer tour has been a little different than it was at this point in 2015. Sure, after five shows this summer we have been treated to a bunch of cool things. The band has kicked down a batch of rarities and bust-outs (particularly enjoyable were “I Am The Walrus”, “Dear Prudence”, and “I Found a Reason”), debuted a remarkable cover in “Space Oddity” and graced us with new Phish songs in “Things People Do”, “Breath and Burning,” and “Miss You."

In addition, there have been a small handful of noteworthy or Jam Chart worthy songs so far (most notably the fantastic “Twist” from Wrigley) but they are coming at a far slower and more measured pace than in 2015. So while Summer 2015 came out of the gates fiercely and quickly, this summer has been a bit more subdued with solid shows yet nothing (yet) that has arisen to the greatness of last summer. Fortunately, Phish can and does turn on a dime and gave glimpses of 2015’s excellence last night in the “Breath and Burning” jam. Mann2 last year was most certainly one of highlights of the summer, and the band loves playing Philadelphia, so many fans of course had high hopes for a repeat of last year’s night 2 at this classic shed.

Photo by Rene Huemer. From @Phish_FTR.

MANN1 RECAP: BREATH & BURNING FUEGO

[Editor's Note: We'd like to welcome guest contributor Dianna Hank for this recap.]

Last night at The Mann Center for the Performing Arts in Philadelphia, PA, Phish decided to show up to their own tour. Now, I’m not saying that there haven’t been good parts of the last 4 shows, it’s just that there hasn’t felt like there was that much cohesiveness between the band members, or flow to setlists. There are certainly things to take away from those shows and jams I will listen to again, but last night was the complete package.

Photo by 215music

MY SUMMER VACATION, BY THE PHISH COMPANION

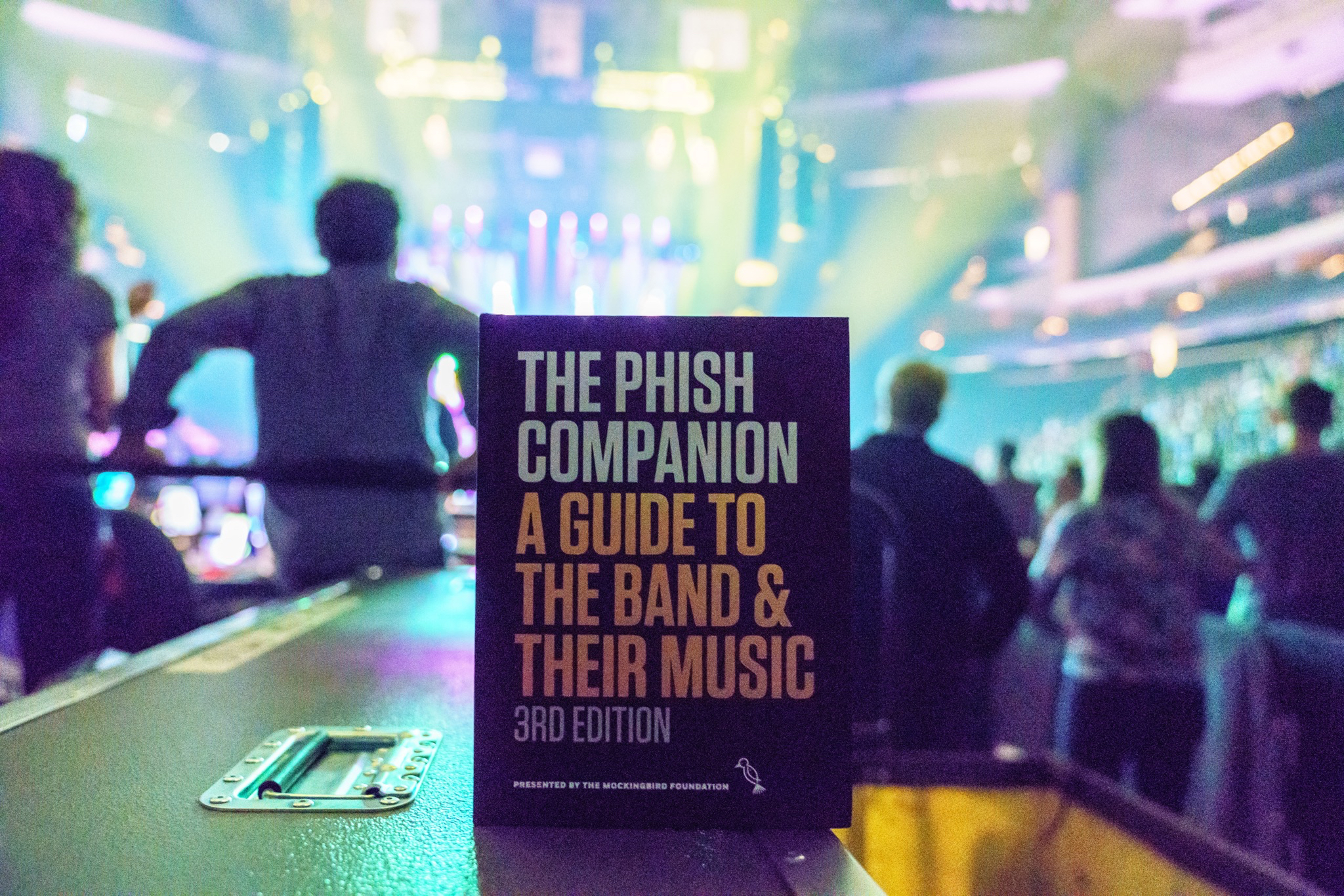

Hi, everybody. TPC3 here to tell you how my summer is going.

I will say my biggest milestone of the summer so far is that I was, like, born. It's good to be out of the womb and into the world but the indignity of the pink safety seat was a bit much to abide. Fortunately, I grew up fast.

MYSTERY JAM MONDAY PART 228

Welcome to the 228th edition of Mystery Jam Monday. This week, we continue with our Hall of Fame Series, when we hand the keys to the MJM command center over to one of the now eight, seven-time MJM winners. For week 2 of this Emeritus Series, we welcome @pauly, the second person forced into mandatory, early retirement after notching his seventh MJM victory.

To Win: Be the first person to identify the song and date of each of the five mystery jam clips, and answer what they share in common. Each person gets one attempt per day, with the second “day” starting after the Blog posts the hint -- each answer should contain five songs / dates, along with the commonality between them. No sharing or trading of answers is allowed. A hint will be posted on Tuesday if necessary, with the answer to follow on Wednesday. The winner will receive an MP3 code good for a free download of any show, courtesy of our friends at LivePhish.com / Nugs.Net. Good luck, and thanks again to @pauly for hosting this second week of the MJM Hall of Fame Series.

NOTE: As a thank you and congratulatory gesture from @ucpete to his (new) MJM Emeritus brethren, he's opted to forfeit his winning code from last week and instead will allow the other MJM Hall of Fame winners to scrap for it in a special MJM: Championship Edition. If one of the MJM Emeritus winners takes down the MJM: Championship Edition, he will win the extra code. If all Hall of Famers fail to take home the extra code, but someone else solve's @pauly's MJM, that winner will take home two codes. The MJM Emeritus winners will refrain from answering MJM 228, and the weekly guessing crew will return the favor by not spoiling the MJM: Championship Edition, but both groups should use the comments section to provide their answers.

@RabeldyNugs, @pauly, @ghostboogie, @bl002e, @PersnicketyJim, @mcgrupp81, and @yunkfunk:>>> MJM: Championship Edition <<<

Hint for MJM 228:

Hint for MJM: Championship Edition: .gnihtemos lleps sMJM tsoM

Answer: It took a five-part, super difficult MJM to get there, but for only the 16th time, the Blog (c/o@pauly) has won! The name of the guy in the picture is "Pauly," just like the MJM savant of yesteryear. The clips?

Piper - 9/17/99

After Midnight - 5/31/11

Undermind - 8/15/11

LA Woman - 12/30/03

You Enjoy Myself - 4/29/94

While the Emeritus crew did a great job stumping the regulars this week, they clearly couldn't handle a taste of their own medicine and didn't even muster a single guess or answer for any of the three clips! So let's do it this way: anyone who can solve the MJM: Championship Edition will win the code I put up for adoption last week -- submit your answer in the comments any time. And next week, we'll play for two more codes regardless. The MJM:CE triple clip (over on SoundButt) already has a hint, and there's nothing dirty about it -- it's three Phish jams from regular shows in wide circulation. Thanks for playing, and we'll see you next week for the next iteration of the MJM Hall of Fame series.

DEER CREEK RECAP: SCRATCHING THAT INDIANA JONES

As we’re now in Phish’s eighth year of their modern incarnation (can you believe it?!), one pattern that has emerged is that the early shows of their summer campaign are mainly used as laboratories for the band, as they attempt to re-assert themselves in new ways on stage while “playing themselves into shape,” so to speak.

This is not to say that they don’t practice before tours or that these shows cannot be entertaining in their own rights (for example, the tremendous 7/24/15 show was the fourth of last summer, and both Wrigley shows and St. Paul had their share of pleasures), as much as it the acknowledgment that a band that improvises music on stage has to do things a bit differently than a band that cranks out most of their new album and a judicious selection of their greatest hits for an hour or so before saying their goodnights. Everyone that’s following the band is waiting for the first “classic show” and “monster jam,” and I have faith that both are coming, while being excited about the shows and jams they’ve given us this year.

WRIGLEY 2 RECAP: LET'S PLAY TWO

Here at Phish.net, we try to tee up recaps from people who were at the show, but sometimes it just doesn't work out and we have to weigh in from the couch. This opens a writer up to the critique that negative opinions expressed are the result of jealousy and sour grapes. In this case, I have no defense to that charge. I’m jealous as all hell that I wasn’t at Wrigley Field this weekend to see the band I love perform in the cathedral that my beloved Cubs call home. Does this mean that any criticism I may be about to level is tainted and biased?

Yes, yes it does.

The first three shows of the tour have felt, to me, like...well, like the early part of a tour usually does. Warming up, stretching things out, not getting too crazy too fast. Saturday’s first set, to my ears, was that process in action. For example, let’s take a couple of standard first set tunes that have been paired seven times, but for the first time, let “Moma Dance” precede “AC/DC Bag.” Let’s mix in some newerFuego material. Let’s sing "Happy Birthday" to the legendary Dickie Scotland, and let’s take a moment to bask in the sunshine of the Friendly Confines on a gorgeous June evening and tell embarrassing stories that you may not have known about Fishman and his dedication to art. Let’s raise our hands to “The Divided Sky” and imagine we’re not on the North Side of Chicago, but in a green field, surrounding a black rhombus, and we’re about to summon something magical. And if Fish flubs the end of “Cavern,” let’s rip through “Good Times Bad Times” and end on that note instead.

FLY, FAMOUS ROCKINGBOOK

Phillip Zerbo, fearless and heroic co-editor of The Phish Companion, took a well-deserved victory lap at the legendary rock venue across the street from his new home. Watch this space in the days ahead as our lil' book makes appearances in other notable locales!

WRIGLEY1 RECAP: THE BAND IN SANTO'S LAND

IT is summer tour again, thankfully, and Phish is once again riding the bus and running the bases. For the first time, Phish played last night at Wrigley Field, the second-oldest ballpark in the majors, wherePage's the beloved Cubs have been playing for 100 years. And also for the first time, Phish performed on a day when global stock markets plummeted, causing countless millions--including those we love--to lose trillions of dollars in retirement and other investments. But enough about Britain's calamitous, sublimely asinine vote to leave the EU. After all, without searing pain and tremendous suffering, there can be no transcendent JOY, and we are blessed to be able to hear Phish's music once again.

Photo by Scott Marks

FAQ: THE PHISH COMPANION, 3RD EDITION

Image by Patrick Jordan

So you’re publishing a book? What is it?

It’s a bound volume full of pages with words and images and charts. But that’s not important right now.

They still have those?

Believe it or not, something like 300,000 new books go into print and over 2 billion books are sold in the U.S. every year.

Wow, that’s a lot!

Indeed. But if you like Phish, this book is the book for you. Total needle-in-a-haystack scenario.

OK, so seriously, what is it?

The first two editions of The Phish Companion (published in 2000 and 2004) were the best sources of comprehensive information about Phish. “Encyclopedical” was a word that had to be invented and dictionarialized just to describe them.

Anyway, if you’re a fan "of a certain age,” there is a pretty good chance you own one or both editions, or at least have seen one at your friend’s house, quite possibly while “dropping off the kids at the pool.” They were about the size of phone books, filled with setlists, text, and charts, all in tiny black-and-white print. The second one has a sea of bros on the cover. A brocean, if you will.

TWIN CITIES RECAP: BUSTING OUT

Today's recap was written by guest blogger and Phish.net user Pete Burgess (@AlbanyYEM)

Tour openers have a certain transformative effect. There are no patterns established yet, no momentum gained or lost, and no acclimation to the normalcy of Phish being on tour. In this rebirth, there is a lightness in letting oneself go from the standards of what has come before and the norms of what one might expect, or perhaps sometimes even feel that one is owed. The joy is in the strangeness. It is a powerful feeling to be swept back into a self that is a little more naïve, a little freer from self-imposed restrictions, and a little more open to that simple joy.

Photo by Rene Huemer via Phish From the Road © Phish

These are my thoughts on the experience of being at this show, but of course a review needs to delve into more than just that aspect. But it is worth bearing in mind as we go through tour with our own analytical tendencies. That said, this was probably the strangest Phish show I’ve been to. From a critical perspective, that strangeness was both positive and negative. The oddness actually worked nicely in this unusual yet slightly understated first set. I have to confess that I did not identify "Pigtail" whatsoever, but the “I’m conscious again” refrain certainly fits the theme of awakening to the possibilities of the new tour.

LIMITED COPIES OF THE PHISH COMPANION TO BE SOLD AT SATURDAY'S PHANART EVENT

The Mockingbird Foundation invites you to visit our table at the PhanArt poster show on Saturday, June 25th from noon to 6:00 p.m. at The Cubby Bear Sports Bar at 1059 West Addison Street in Chicago, across from Wrigley Field.

Along with more than 20 other artists and vendors exhibiting a wide variety of unique and Phish-inspired creations, fans will also be able to peruse the new Phish Companion -- and even buy the sucker for the online price of $39 while supplies last. (We will only have a limited number of books to sell at the show, but we will honor all purchases made in person Saturday at the special show price of $39 with free delivery; those books will ship immediately after the show).

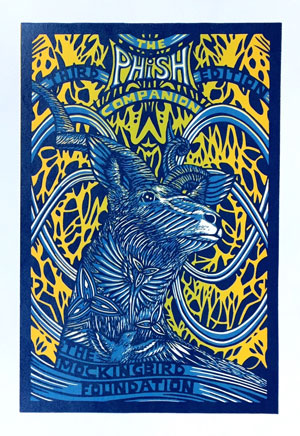

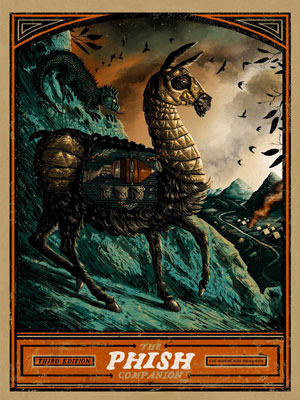

We are also thrilled to be offering, for the first time, two new posters commissioned from well-known artists Isadora Bullock (“Out of Control”, left) and Zeb Love (“Sunrise Over the Turquoise Mountains”, below).

Bullock’s “Out of Control” is a hand-crafted linoleum cut print in a signed and numbered edition of 150. The artist will be at the Mockingbird Foundation table from 1:00 to 2:00 p.m. to meet fans and personalize prints. A very small number of special print variants will also be available.

Also debuting is Zeb Love’s spectacular new print, “Sunrise Over the Turquoise Mountains”, to celebrate the release of The Phish Companion. Zeb is well known on the rock poster art scene, and as this is his first Phish-related piece, we are honored to have him work with us. “Sunrise” is a screen print, in a signed and numbered edition of 175. A very small number of “Sunrise” print variants will also be available.

We will also have for sale limited edition clothing inspired by art from The Phish Companion: two lightweight numbered basketball jerseys produced by a collaboration between Boyer Design and artists David Welker and AJ Masthay. Supplies of these custom jerseys are also limited.

Admission to the “PhanArt in Harry’s Hood” show is free and there will be food and beverages available and music by Wyllys.

Further information about the PhanArt show is available on the PhanArt website and its Facebook event page.

MYSTERY JAM MONDAY PART 227

Welcome to the 227th edition of Mystery Jam Monday. Beginning this week and continuing throughout summer, we will be honoring our lifetime MJM champions, that elite group of seven contestants who each won MJM on seven separate occasions, thereby necessitating retirement from active competition. Each week, we'll give one of these emeritus winners the chance to select the MJM, and pit their proven knack with today's crop of top notch talent. To make things even more interesting, our very own host,@ucpete, has temporarily vacated his post, so that he can get back in the action, hoping desperately to eek out that elusive 7th win, so that he too can join the ranks of the Legendary. But ol' Pete has some tough competition from the likes of other 6 time winners, @schvice and @WayIFeel. Who will reach the top of Mt. Icculus first? Perhaps, it will be this week's guest MJM trickster, the first and all-time leading MJM Champion – welcome @RabeldyNugs:

"It's such an honor to be a part of this elite group, even though I miss out on the fun every Monday. Monday just hasn't been the same since being 'voted' into this Hall of Fame, so to speak. I wish everyone the best of luck, though not so much during my watch. And be safe on Tour."

To Win: Be the first person to identify the song and date of each of the five mystery jam clips, and answer what they share in common. Each person gets one attempt per day, with the second “day” starting after the Blog posts the hint -- each answer should contain five songs / dates, along with the commonality between them. No sharing or trading of answers is allowed. A hint will be posted on Tuesday if necessary, with the answer to follow on Wednesday. The winner will receive an MP3 code good for a free download of any show, courtesy of our friends at LivePhish.com / Nugs.Net. Good luck, and thanks again to @RabeldyNugs for hosting our kick off week of MJM Hall of Fame Hosts.

Hint: "There are only patterns, patterns on top of patterns, patterns that affect other patterns, patterns hidden by patterns, patterns within patterns. If you watch closely, history does nothing but repeat itself."

- Chuck Palahniuk

Answer: Now comes seven time winner @ucpete, stepping into the winner's circle one final time, before taking his seat with the Pantheon of Elders. Navigating a treacherous, obstacle-ridden course set by all-time MJM champion @RabeldyNugs, Pete correctly identified the tracks (8/15/93 Tweezer,7/1/98 Tweezer, 6/10/00 Jam after Gin, 12/8/94 Possum, and 8/10/04 AC/DC Bag), and theme (jams from shows containing jams with which @RabeldyNugs won previous MJMs). This Iditarod-like quest was replete with challenges, even for the veteran players. The double lead-off Tweezer sent at least a few folks chasing Tweezers for a theme. Meanwhile there's something rotten in Denmark, and that smell apparently caused @WayIFeel to take a wrong turn in Copenhagen. Another presumed contender, @schvice, was stuck in the sled shop and never hit the trail in time to make a serious race for the crown. As a final trap intended to ensnare all but the most worthy, the third track, a "song" listed on the tape from 6/10/00 as "Jam" (after Bathtub Gin and before Twist) is not included on the PhishTracks or Phish.in' recordings for this show, but is included on the Spreadsheet version. To further complicate matters, our friends on the Setlist team have not characterized this 2:39 piece of music as a "Jam," so a quick search of @RabeldyNugs's winning shows doesn't yield any helpful pointers.

Congrats to Pete, thanks again to @RabeldyNugs for leading off the Hall of Fame Guest Host Series, and I hope everyone had fun this week, just in time for the beginning of Tour. Be sure to tune in next Monday, when our next guest host, @pauly throws down the gauntlet for MJM 228.

The Mockingbird Foundation

The Mockingbird Foundation